Which came first: the chick or the egg?

Adult kiwi set up a territory, prepare a nesting burrow and then mate. When the female produces her huge egg (or two), in some species like the North Island brown kiwi, only the male incubates it. When the egg hatches, a fully feathered chick emerges to face its first few days of life.

Territory

A male kiwi needs a territory before he can attract a mate.

Male kiwi fiercely protect their patches, so fights can be very rough. They involve high jumps and slashing blows, kicks and tears. A kiwi’s sharp claws and powerful legs and feet can inflict fatal wounds.

Once territories are established, border disputes are usually resolved by less dangerous means. Birds call to mark the edge of their territory and the sound can carry several kilometres. To avoid a confrontation, kiwi speed back into their home zone before returning their neighbour’s call.

Territory size

The size of territories ranges between two and 100 hectares, depending on the species and their location. For example, Rowi and Haast tokoeka have the largest territories: up to 100 hectares. The size of the Stewart Island tokoeka’s territory varies depending on food supply. In the leaner coastal sand dunes, family groups can command 50 hectares, while in food-rich tussock grassland of Mason Bay, just five hectares will do. Stewart Island tokoeka are unusual among many kiwi varieties because they live in small mixed-age family groups.

Finding a mate

Kiwi are unusual among birds because once they’ve bonded as a pair, they usually stay together as a life-long monogamous couple. Traditional gender roles are reversed. Fhe female is bigger and dominates the male. This is also extremely rare among birds.

Mating

Once bonded, a kiwi pair is usually monogamous.

Kiwi partnerships have been known to last longer than 20 years. Every third day or so the pair comes together to share a burrow, and at night they perform duets, calling to each other.

Divorces also happen, especially in high-kiwi density areas in Northland. Divorces can be caused by breeding failures or if birds are young and early in their breeding career.

Breeding season

The main breeding season runs from June to March when food is most plentiful. The exception is brown kiwi in the North Island, which can lay eggs in any month.

In captivity, male kiwi can reach sexual maturity at 18 months, while females can lay their first eggs when they’re about three years old. In the wild, kiwi usually do not breed until much older. Wild females lay their first eggs at 3-5 years of age.

In rowi, Operation Nest Egg has changed some breeding behaviour. Birds that are re-released into their wild home tend to breed at an earlier age than those raised by their parents. It is thought that this is because wild-raised rowi live in family groups, with young birds staying in their parents’ territory for several years to help raise their siblings. Operation Nest Egg breaks these family ties, which means young birds released back into the sanctuary are free to mate sooner. The positive result is that Operation Nest Egg birds are helping boost rowi’s small population more quickly.

Mating behaviour

With no colourful plumage or a beautiful song to attract his mate, the male kiwi has developed the strategy of persistence. He follows her about, grunting. If uninterested she may run away, or use her greater weight and size to see him off. However, if she is interested, mating takes place, three or more times a night during the peak of activity.

The male taps or strokes the female on her back, near the base of her neck. She crouches low with her head stretched forward and resting on the ground. Because the female is the larger bird, the male needs her full co-operation. He climbs onto her back, which can be difficult with no wings or tail to help him balance. Often he will grasp her back feathers in his beak to help his balance.

The kiwi female calls the shots during mating. If she loses interest she may wander away, leaving the male in an undignified heap on the ground.

Two functional ovaries

Another unusual thing about kiwi is that females have two functional ovaries. In most other birds only the left ovary develops. Only brown kiwi regularly lay more than one egg in a clutch, but when this occurs, ovulation happens in each ovary.

Incubating the egg

Until recently, it was thought that only male kiwi incubate eggs.

New information about the social systems of the different kiwi varieties tells a different story. Not only do some taxa share incubation, but not all of them live simply as pairs.

Only in the little spotted and brown kiwi species are eggs incubated just by the male parent. These species also live in pairs.

However, new information shows that both parents in the great spotted kiwi, rowi, and tokoeka varieties share incubation to some extent.

Not only that, with Stewart Island tokoeka young birds stay in their parents’ territories for several years and help raise their younger siblings, with Stewart Island tokoeka helpers even sharing in the incubation.

Sub-adult great spotted kiwi living in the mainland island at Lake Rotoiti in the Nelson Lakes National Park have also been found near their parents and may help guard chicks against predators.

Lonely vigil

Kiwi that incubate eggs develop a bare patch of belly skin, known as a brood patch. Free of feathers, it exposes warm blood vessels close to the surface that are ideal for keeping the egg warm.

The adult uses its long beak to keep the egg tucked beneath it. If the female kiwi lays a second egg, the nest can become crowded and eggs do get accidentally broken under the parents’ large feet.

If the male kiwi incubates the egg alone, he leaves the nest unattended to feed. Early on he can leave the nest for most of the night, covering the eggs and burrow entrance with litter.

Sometimes the male will bathe when out feeding. It is thought his damp feathers help maintain the correct humidity in the nest.

Close to hatching, the adult will sit tight for several days at a time, sustained by fat reserves. By the time the egg hatches, the adult will have lost a great deal of body weight.

A long incubation period

Kiwi invest a lot of energy in incubating their eggs. The average incubation time is 70-80 days, more than twice what’s normal for most birds and about the same as the gestation period of a similar sized mammal.

It was once thought the incubation period was so long because the egg was too big for the kiwi to incubate properly. Now it seems more likely that it is due to the kiwi’s low body temperature.

The young bird

Kiwi chicks hatch as mini-adults. They’re fully feathered, open-eyed, and have soft, pink beaks.

Kiwi parents do not need to feed their young because chicks can survive off the rich egg yolk for several days. At the end of this time, a kiwi chick may weigh only 80% of its hatching weight.

Leaving the burrow

After two or three days, enough of the yolk sac has been absorbed into the kiwi’s body to allow it to stand and shuffle around the nest. On about day five, it begins to venture out of the burrow.

The kiwi chick initially does not go far from the nest, and eats only pebbles and tiny twigs that will be stored in its gizzard to help with food digestion.

On its second trip out of the burrow, the chick eats its first meal. Because its beak is not yet strong enough to dig into the ground, it forages in the leaf litter.

All this time it continues to draw nourishment from the yolk sac, and can easily survive two weeks of partial fasting.

Vulnerable to predators

During its first three-to-four weeks, the baby kiwi mostly feeds at night, and sometimes during the day. This makes it extremely vulnerable to predators. Around 90% of kiwi chicks born in the wild die within their first six months, 70% of them killed by stoats and cats. Only about 5% of kiwi chicks survive to adulthood.

Leaving home

Young kiwi continue to grow slowly until they are about four years old. When they leave home depends on the social system for each variety. For example, some brown kiwi leave their parents’ territories when they’re 4-6 weeks old and are fully independent, but great spotted kiwi juveniles stay in their parents’ territories for a year or more. Stewart Island tokoeka and rowi can remain with their parents for up to seven years, helping raise their siblings.

Whichever the taxa, when the young birds are old enough to establish territories and find a mate, the cycle begins again.

Kiwi are potentially very long-lived, with some individuals living for 50-60 years. Research has not been going on long enough to be sure.

The burrow

Once kiwi have established a territory and formed a pair, the business of breeding begins.

Building a burrow

Kiwi may dig their nesting burrows up to two months before their first egg is laid. Sometimes they use an existing nest.

The burrow is usually lined with an untidy nest of soft leaves, grass and moss. When inside, kiwi often pull leaves and sticks across the entrance as camouflage and to retain heat and moisture.

Different types of burrow

Kiwi can have as many as 50 burrows dotted across their territory. These take many forms, depending on the species and the location.

The birds can use their strong legs and claws to dig a burrow in the earth of a bank or slope. During the day, their shelter may simply be in a hollow tree, under a log, in a rock crack, or within a dense clump of vegetation.

Great spotted kiwi prefer dens to simple burrows. Unlike the little spotted kiwi and the brown kiwi, which tend toward simple one-entrance burrows, the great spotted kiwi will put time and effort into constructing a labyrinth of tunnels several metres long, and with more than one exit.

Sleeping

A kiwi sleeps standing up. Like many birds, it often turns its head back against its body and tucks it under its wing. However, unlike other birds that have big wings and small beaks, this posture can make the kiwi look slightly ridiculous. Its 20-centimetre beak does not easily tuck under the tiny crooked stump of its vestigial wing!

Producing an egg

It takes 30 days for a female kiwi to develop an egg inside her.

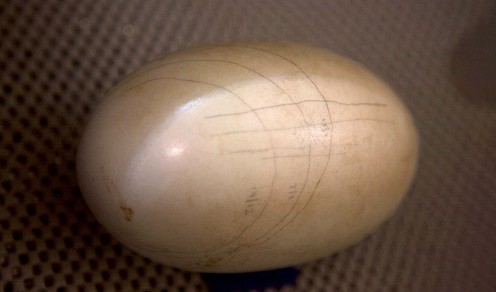

Its smooth, thin, white or greenish-white shell is about 120 millimetres long and 80 millimetres in diameter.

Because of their size, kiwi could be expected to lay an egg about the size of a hen’s egg. In fact, the kiwi egg is six times bigger than other birds of a similar size. They are almost exactly the same size as eggs produced by the now-extinct bush moa, a much bigger bird. This has led to speculation about whether the kiwi was once a much larger bird.

Kiwi eggs also contain the largest proportion of yolk of any bird: 65% compared with 35-40% for most other birds. Kiwi chicks hatch with a large external yolk sac, which is gradually absorbed through their navel, over their first 10 days of life. This is why kiwi parents do not have to feed their newly hatched chicks.

Huge effort to produce a huge egg

To produce such a large egg, the female kiwi must eat three times as much as usual during gestation.

The egg grows to take up 15-20% of her body mass and her pregnant belly bulges so much it touches the ground. The female has to walk with her legs wide apart to accommodate it. Sometimes a female will soak her belly in cold water to soothe the inflamed stretched skin and temporarily relieve the weight.

Just before the egg is laid, it takes up so much room inside the female there is little left for food and she will fast for two or three days before laying.

Most clutches are one egg

In most kiwi varieties, the typical clutch size is one egg. The exception is brown kiwi which usually lay two eggs in a clutch – sometimes even three.

Although enormous, the egg is laid quickly and for brown kiwi and little spotted kiwi females their work is then done. She leaves the burrow and the male takes over incubating the egg. In the other kiwi varieties, the male and female kiwi share incubation.

In two-egg clutches, the second egg will already have begun to develop inside the female and will be laid about 25 days after the first. It is rare but not unknown for a third egg to be produced, especially if one of the first eggs is lost or collected as part of Operation Nest Egg. The most prolific egg producer is the brown kiwi, which will often lay two-to-three clutches each year.

A female kiwi can lay up to 100 eggs in her lifetime.

Hatching

Hatching is an exhausting process that can take up to three days.

Unlike other birds, kiwi chicks don’t have an egg tooth which means hatching is a very exhausting job of kicking and pecking its way out.

The first sign that the chick is ready is when the egg jiggles slightly. It may stay still for 20 minutes, then jiggle again.

Eventually the chick will make a tiny hole in the air-filled sac inside the end of the egg, poke the pink tip of its beak through, and breathe air for the first time. Following this exertion, it may sleep for anything from 12 to 48 hours.

When it awakes, the chick tries again, kicking and pushing against the shell wall, which flexes as the baby bird struggles inside, mewing loudly. Eventually a crack or hole appears and the chick’s beak pokes through the shell. As the shell slowly cracks open, the chick continues to struggle off and on, until at last it is free. The hatching process can take up to three days.

The parent stamps on the empty shell and buries it in the nest or eats it to regain some lost calcium.

If a second egg has been laid in the clutch, this hatches faster than the first egg. The first chick can be anywhere between one and three weeks old when the second chick arrives.

Massive yolk to nourish the chick

Kiwi chicks hatch with a large external yolk sac which is gradually absorbed through their navel over their first 10 days of life. This means they do not have to go outside to feed for the first few days. Although born with huge feet, chicks often can’t stand up because their bellies are so distended by the yolk sac.

Unlike chicks of other birds, the newly hatched kiwi is not covered in down. Instead, its feathers are covered in a slimy coat that dries and flakes off within 24 hours, leaving the chick a miniature version of its parents.

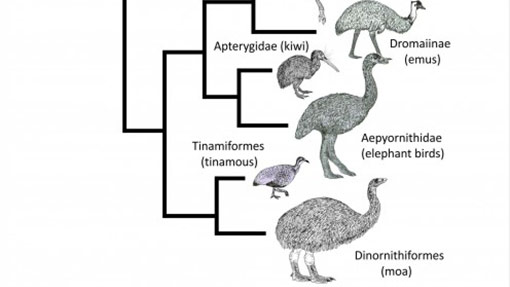

Part of the ratite whānau

Kiwi are part of a group of largely flightless birds known as ratites. Ostriches, emu, and the extinct moa are also part of this group.

Honorary mammals

The kiwi is sometimes referred to as an honorary mammal because of its un-birdlike habits and physical characteristics.

The hidden bird of Tāne

In Māori tradition, all living things on Earth originate from the union of Rangi-nui (the Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (the Earth Mother).

Flightless ... but has wings

The kiwi is one of New Zealand's many flightless birds. They didn't need to fly because there weren't any land mammal predators before man arrived to New Zealand 1000 years ago.

Feathers like hair

Because kiwi do not fly, their feathers have evolved into a unique texture to suit a ground-based lifestyle.

An unusual beak

The kiwi has an extremely unusual beak. Not only does it provide a keen sense of smell, it also has sensory pits at the tip which allow the kiwi to sense prey moving underground.

Enormous egg

In proportion to its body size, the female kiwi lays a bigger egg than almost any other bird. While a full term human baby is 5% of its mother's body weight, the kiwi egg takes up 20% of the mother's body.

Kiwi life cycle

Kiwi make their home in many different environments and have been described as 'breeding machines'. With the eradication of predators, the kiwi could be successful once again.

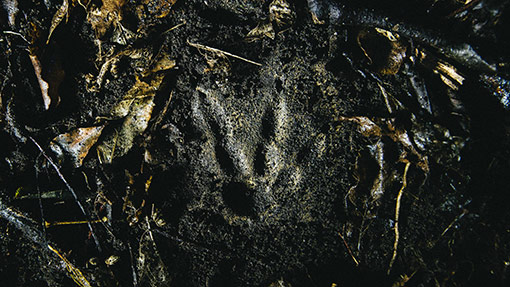

Kiwi signs

Being nocturnal, kiwi can be quite elusive but they do leave signs as to where they have been.

Bird of the night

Kiwi are nocturnal. Like many other New Zealand native animals, they are most active in the dark.

Kiwi calls

Kiwi call at night to mark their territory and stay in touch with their mate. The best time to listen for kiwi is on a moonless night, up to two hours after dark, and just before dawn.

What kiwi eat

Kiwi are omnivores. Their gizzards usually contain grit and small stones which help in the digestion process.

How kiwi came to Aotearoa

Just how did the kiwi journey to New Zealand? Three very different theories have been put forward to explain the mystery.

How kiwi evolved

It is thought that today’s kiwi evolved from one kiwi ancestor that lived about 50 million years ago: a proto-kiwi.

Kiwi myths

Kiwi experts are keen to dispel myths surrounding the kiwi - and there are quite a few!

Learn more about kiwi

Kiwi species

All kiwi are the same, right? Wrong. There are actually five different species of kiwi, all with their own unique features.

Threats to kiwi

The national kiwi population is under attack from many different threats, including predators, loss of habitat, and fragmentation of species.

Where to see kiwi

Many facilities around New Zealand are home to kiwi, plus there are places where, if you're lucky, you could see one in the wild too.

How you can help

Many hands make light work. Keen to join the mission to save the kiwi? Here are some ways you can help.

Protect kiwi

For kiwi to thrive, we all need to work together. Find out what you can do to help save the kiwi, wherever in Aotearoa you happen to be.

Fundraise

To continuing saving the kiwi, conservation groups need funding. Support the mission by making a donation, setting up a fundraising project, or engaging with other fundraising initiatives.

Shop for kiwi

Show your support for Save the Kiwi and some of our wonderful sponsors by purchasing products that will help us do more of what we do.

Donate

Make a quick donation, donate a day of annual leave or invest to save the kiwi.